Reverter: A gift of land recalls its purpose.

SANTA ANA, CA–J. E. “Ed” Prentice came to Orange County in the early days, when it was just a farm belt dotted with a few small towns and whistle-stops.

He had been a teacher, lawyer, and sometimes farmer in his native Kansas when, in 1912, he and his wife Edith came west.

They settled in Santa Ana, the county seat, and Ed got into business trading mules and horses. He owned a stable in town and folks called him “Judge.” At home, he kept a pet monkey.

By the 1920s, Ed was busy buying orange groves and making farm loans from an office he occupied in the First National Bank Building. He now had four pet monkeys.

Then came the depression.

It was 1931 and Ed, now 44, held a mortgage against the Melwood Estate on the outskirts of town. Melwood was 19.23 acres with a sixteen room mansion, a producing orange grove, water plant and packing shed. The owner was in dire straits, and the mortgage was in default. Ed foreclosed and got the property for $12,600.

Ed and Edith, who were childless, moved in at Melwood with Ed’s monkeys. There, they rode out the depression until 1940, when Edith died. After that, Ed lived alone with a succession of servants who, tormented by monkeys, kept quitting.

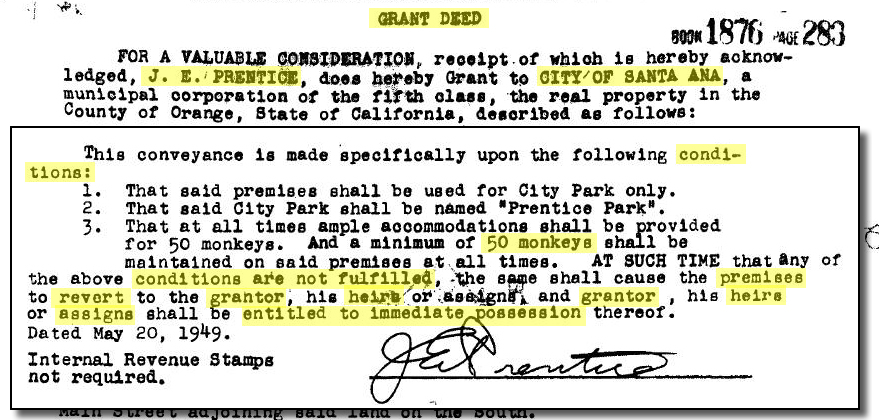

By 1949, the Melwood grove was in decline and suffered from disease. Ed got the idea to give some land to the city for a park. The gift was accepted, and a deed was recorded conveying twelve acres to the City of Santa Ana, with “conditions.”

The deed conditions were that the land was to be used for a park only, to be named “Prentice Park,” and “at all times ample accommodations shall be provided for 50 monkeys.” If the monkey population should fall below 50, the land would automatically revert to Ed or his heirs.

The Santa Ana Zoo at Prentice Park opened in 1952. Ed continued to live next door, but he became irritated that city officials underfunded the park and it looked shoddy. He called them “knuckleheads,” and grumbled that they should return the zoo to him so he could run it.

Eventually Ed moved away, and in 1959 he died at age 81.

For more than 50 years all went well at the zoo. Monkeys played and children came to ogle. Then, in August 2008, the city got a letter from an attorney representing one Joseph Powell, a grand-nephew of J.E. Prentice. The letter demanded proof that the zoo had 50 monkeys or, the letter said, “we plan to proceed with our rights under the grant deed to have the property revert back to Mr. Prentice’s heirs.”

It seems the cagey Mr. Powell had visited the zoo and counted monkeys. There were only 49, he claimed, after the death of a 35-year-old silver langur named Geni. Within months, the count dropped again with the death of a capuchin named Monty.

The City Council began to fret. Healthy monkeys, to live in captivity with others of their endangered species, are hard to come by. International rules have to be followed.

Then a wondrous thing happened. The little monkeys rose to the legal challenge mounted by Powell, and a golden lion tamarin named Maya gave birth to twins.

In ensuing months, a pair of crested capuchins named Romeo and Juliet added another offspring, bringing the monkey population to 51.

And zoo officials aren’t sitting on their tails, either. They announced they will build their collection of “bona fide” monkeys (no lemurs or gibbons) to at least 55. Romeo and Juliet are, after all, on loan from Brazil.

Moral: The reverter clause is legally enforceable by the Prentice heirs (and who knows how many there are), so this monkey census is serious business.

The stakes are high. The twelve acres in central Orange County are now worth millions.

It comes down to law; the law of the jungle.