A fixed easement blocks development.

WASHOE VALLEY, NV–Washoe Valley lies east of the Sierra Nevada mountains, midway between Reno and Carson City. It’s a scenic place, with native pines, panoramic views and, until recently, few residents.

But with a gaming capital up north, and the state capitol to the south, Washoe Valley is attracting developers who want to exploit its obvious growth potential.

The push for “growth” has been strongly opposed by long-time residents, who fear losing their rural lifestyle and dread “urbanization.”

Battle lines have been drawn, and in the face of local opposition developers have gone to court to advance their interests. Some have filed lawsuits to force municipal entitlements, such as water and sewer services, for new subdivisions.

One prominent developer here is St. James Village, Inc., owner of a 1,600 acre project known as “St. James’s Village.” St. James’s Village is a master-planned gated community of custom homesites, on acre-sized lots.

On St. James’s drawing board is a plan to subdivide one of its parcels into 28 lots. This parcel is adjacent to lands owned by families named Cunningham and Saladin (collectively, the Cunninghams).

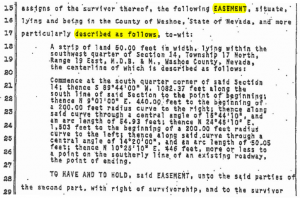

In 1974, a predecessor of the Cunninghams acquired an easement over what is now the St. James parcel to provide access for the Cunninghams’ properties to an existing road, now known as “Joy Lake Road.” The deed creating this easement used a metes and bounds description, making it clear where the easement would be located on the ground.

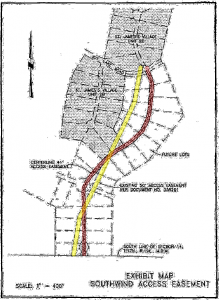

In drawing their subdivision plan, St. James determined they would have to relocate the 1974 easement in order to create 28 buildable lots, instead of a lesser number. So the plan was drawn with a curved road to replace the easement, still connecting Joy Lake Road to the Cunninghams’ properties.

The St. James Parcel, showing Joy Lake Road (top), the 1974 easement (yellow), and the proposed relocated road (red). The Cunninghams' properties are lower right (not shown). (Click to enlarge.)

Problem was, the Cunninghams would not agree. So St. James filed a lawsuit against the Cunninghams, contending “property owners can unilaterally relocate easements, if such relocation does not materially inconvenience the easement holder, in order to allow the development of their property.”

The Cunninghams responded, denying “inconvenience” as the issue, and instead asserting an absolute right to keep the easement in place based on Nevada case precedents. Mainly, the 1969 case of Swenson v. Strout Realty, Inc., holds that location of an easement, once selected, cannot be changed by either the owner of the burdened property or an owner of benefited property without consent of the other.

The trial court ruled for the Cunninghams, and the case headed up to the Nevada Supreme Court.

While acknowledging Swenson and other precedents, the Supreme Court said the traditional rule no longer reflects public policy, and it fails to fairly deal with interests of a land owner and easement holder as they may change over time.

So the Court announced a new rule, holding an easement may be unilaterally relocated when no one’s rights will be impaired; except that an easement created with an agreed-upon location or dimensions cannot be changed without mutual consent of the land owner and easement holder.

In this case the 1974 easement was created with a fixed location and dimensions, so it can’t be relocated by St. James acting unilaterally. Back to the drawing board.

Moral: This new rule in Nevada follows a modern trend to allow relocation of easements, while giving deference to the intentions of parties who created the easement.

This is basic contract law, and it hews to the rules of interpretation of contracts. It’s a little known secret that much of “real estate law” is simply contract law, applied to real property.

The case is St. James Village, Inc., v. Cunningham, 210 P.3d 190 (Nev. 2009).