The case of the misfit mortgage.

BESSEMER, AL–Davis & Associates, LLC, was the owner of two lots in Jefferson County, Alabama.

BESSEMER, AL–Davis & Associates, LLC, was the owner of two lots in Jefferson County, Alabama.

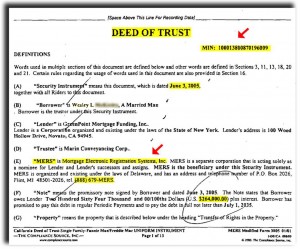

Davis & Associates borrowed $43,000 from Frank Bynum, giving Bynum a mortgage against the lots. The mortgage identified the borrower as “Davis Associates, LLC.” The mortgage was recorded in the land records maintained by the Jefferson County Probate Office.

Later, Davis & Associates conveyed the lots to TMS Properties and, a few months after that, TMS Properties conveyed the lots to Angel Barker. Ms. Barker purchased the lots with a loan secured by a mortgage held by GMAC Mortgage.

Meanwhile, Davis & Associates failed to repay the loan from Bynum, and Bynum threatened foreclosure.

But Barker and GMAC said they didn’t know about the Bynum mortgage. So Barker and GMAC filed suit for a judicial declaration that they were bona fide purchasers of the lots, without notice of the Bynum mortgage, and not subject to it.

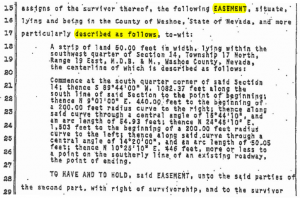

In court, Barker and GMAC said the incorrect name on the Bynum mortgage (“Davis Associates” rather than “Davis & Associates”) caused the mortgage to be mis-indexed in county land records.

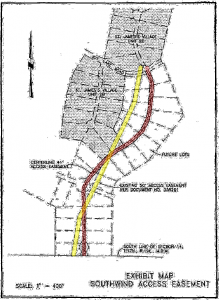

As provided by Alabama statutes, the land records consist of a grantor-grantee index, containing names listed alphabetically, maintained by the county probate office. In 1984, the Jefferson County Probate Office converted its paper index books to a computer database. Expert witnesses testified that a search of the computer database for “Davis & Associates” does not turn out the Bynum mortgage, because of the missing ampersand.

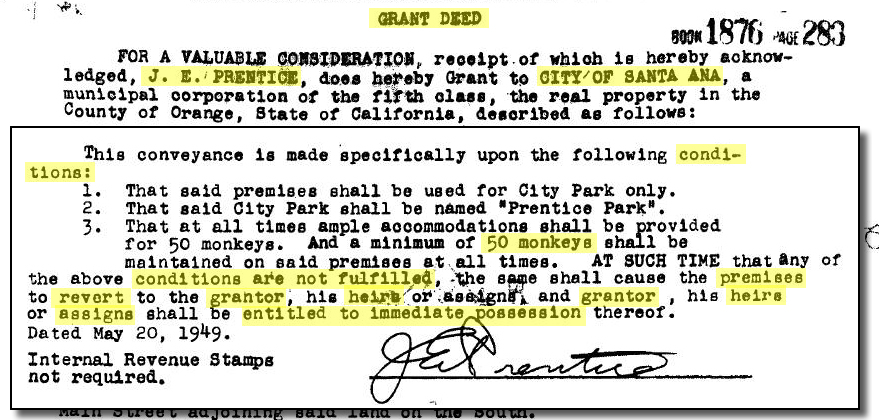

Bynum argued that all duly recorded documents become part of the land records, and impart constructive notice whether or not they are properly indexed in the computer database. It follows, said Bynum, that Barker and GMAC had constructive notice of the mortgage and are subject to its enforcement.

You’re the Judge: How do you rule?

The Alabama Supreme Court ruled in favor of Barker and GMAC.

The Court reasoned that the county land records were set up and maintained in full compliance with state statutes. Persons relying on this index should not be charged with notice of recordings that can’t be found by searching a correct name.

Since the missing ampersand caused the Bynum mortgage to go undetected, the Court held the mortgage was outside the chain of title for Davis & Associates. So the mortgage did not impart constructive notice, and it cannot be enforced against Barker or GMAC.

The case is Bynum v. Barker, 39 So.3d 1013 (Ala. 2009).