Fraud victims compete for priority.

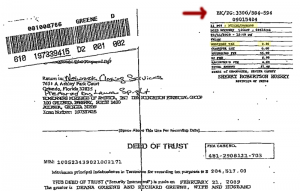

SOUTH GATE, CA–On Thursday, August 28, 2008, Ms. Kyung Ha Chung gave a deed of trust against her property on Roosevelt Avenue. It all went so smoothly she repeated the process that day, eventually signing six deeds of trust against the same property, in favor of six different lenders and witnessed by six different notaries.

The next day, August 29, Ms. Chung signed a seventh deed of trust. Each lender believed it had a first mortgage. All told, the seven deeds of trust secured loans totalling $1,827,500. The property was worth maybe $300,000.

Of the seven deeds of trust, the first three submitted for recording were received by the Los Angeles County Recorder’s office in batches from different title companies around 6:00 a.m. on September 4, 2008. One was in favor of First Bank, another in favor of East West Bank, and another in favor of Flagstar Bank.

The L.A. County Recorder’s office processes thousands of documents each business day. Once received, each document is referred to an examiner to make sure it’s suitable for recording, and then to a cashier to collect applicable fees. If accepted the document is stamped with a recording date and time, and an instrument number. It is later indexed and becomes part of the official land records.

All three deeds of trust were accepted and stamped as recorded on September 4, 2008. As is done in most California counties, the Recorder gave the documents an 8:00 a.m. time stamp because they were deposited before office hours. The East West deed of trust was indexed before the others, at 11:26 a.m. that day.

Los Angeles County Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk's building at Norwalk, California. This is the Recorder's main office; there are five branch offices

It should come as no surprise that all seven loans defaulted, and the lenders discovered they’d been scammed. Some commenced foreclosure, and a dispute arose as to which lender had priority.

Eventually, First Bank filed suit for a court order that the three deeds of trust should have equal priority because they share the earliest recording date and time. But East West opposed the suit, claiming it alone should have priority because its deed of trust was indexed before the others.

The trial court ruled in favor of First Bank, and East West appealed.

The Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court, based on California’s “law of priorities.”

The Court explained that, under state recording laws, priority of interests in land depends on a combination of factors. One gains priority by (a) acquiring an interest as a bona fide purchaser, for valuable consideration, without actual or constructive notice of (b) a previously created competing interest of another party, and (c) being first to record his interest in the land records. This is commonly known as a “race-notice” system, to be distinguished from “pure race” rule giving priority to the first to record.

In this case the Court deferred to the Recorder’s administrative system of assigning recording dates and times, and said the First Bank and East West deeds of trust were recorded “simultaneously” at 8:00 a.m. on September 4. Indexing, the Court said, is a separate function done not to affect recording times but instead to impart constructive notice. Since “both trust deeds were executed on the same day and are deemed recorded simultaneously,” and neither lender had notice of a competing interest, the Court concluded the deeds of trust have “equal priority.”

Moral: This decision gives a good explanation of California’s race-notice recording laws, and is a case study of how the rules apply. Flagstar Bank did not participate in the appeal, due to some procedural issue, but it should benefit by this decision.

What’s curious is how the scammer was able to pull this off. Most lenders and title companies now have systems to detect redundant loan applications and open title orders involving a single property. This plot should have been foiled before the loans funded.

And what do we know of Kyung Ha Chung? It’s possible she was an impostor, using an alias or stolen identity–although the Court seems to believe otherwise.

The case is First Bank v. East West Bank, 199 Cal.App.4th 1309 (Cal. App. 2011).