When you own land, you need a right of access.

VALPARAISO, IN–In August 1985 John and Susan Hall acquired two parcels here in rural Indiana, one fronting County Road 50 North and the other 800 feet to the rear. Neighbors to the east were John’s brother and his wife.

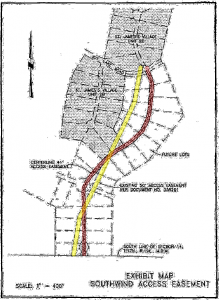

The rear parcel, shown highlighted, with the front (Wilusz) parcel above it and the eastern (Luna) parcel to its right. The public road is at the top of this image.

John and Susan soon mortgaged the front parcel and built a home.

Our story continues in 1998, when John and Susan were delinquent and their mortgage lender, First Federal Savings, filed a judicial foreclosure action. In March 1999, the front parcel was sold at sheriff’s sale and promptly resold to William and Judith Wilusz.

John and Susan remained owners of the rear parcel, about two acres, which was undeveloped. By 2007, they determined to sell the property but, problem was, there was no legal right of access to connect it with the public road. The Wiluszes would not grant an easement over the front parcel, and the eastern parcel was now owned by Benjamin Luna who likewise denied the Halls’ plea for an easement. So the Halls filed suit against the Wiluszes and Mr. Luna, seeking an “easement of necessity.”

The trial court ruled in favor of defendants Wilusz and Luna, reasoning that the Halls had failed to arrange for access when they easily could have, and waited too long to raise the issue with innocent newcomers Wilusz and Luna. The Halls appealed.

The Court of Appeals reversed in part (against Wilusz), and affirmed in part (for Luna).

The Court explained that an easement of necessity may arise, by implication, when land under a “unity of title” (having one owner) is divided “in such a way as to leave one part without access to a public road.” In such a case, the law presumes an intention of the owner that none of the land be made inaccessible by the division.

In this case, the effect of the mortgage against the front parcel, and subsequent foreclosure and sale to Wilusz, was to render the rear parcel inaccessible. It follows that an easement of necessity was created, by operation of law, over the Wilusz parcel at the time the Halls’ ownership of the two parcels was “divided,” and this easement benefits the rear parcel indefinitely even as one or both parcels are acquired by new owners.

The Luna parcel, on the other hand, was never owned by John and Susan Hall and, the Court said, “an easement of necessity cannot arise against the lands of a stranger.”

Moral: Key words here are “easement by implication,” and “unity of title.” The common law favors productive use and enjoyment of land, hence this rule to preserve rights of access when lands are divided and dealt off.

A legal right of access to land is typically covered by title insurance, at least in subdivisions and established neighborhoods. But real estate buyers and investors should always assure themselves that covered or “legal” access meets expectations.

The case is William C. Haak Trust v. Wilusz, ___ N.E.2d ___, 2011 WL 1842735 (Ind. App. 2011).