An unattested mortgage, even when recorded, fails its purpose.

ALPHARETTA, GA–On October 12, 2005, Bertha Hagler refinanced her home.

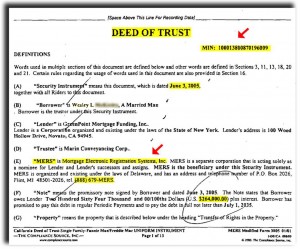

She signed two security deeds (akin to a mortgage): A “first” securing repayment of $240,000, and a “second” for a lesser amount. But at closing somehow things got confused, and only the “second” got signed by the notary and witness who were there.

Weeks later when the security deeds were recorded no one noticed that the “first” was not properly attested to.

In April 2007 Bertha filed Chapter 7 bankruptcy, and a trustee in bankruptcy was appointed. The trustee noticed the defective security deed, and filed an adversary proceeding to avoid it as against Bertha’s home.

The trustee relied on Bankruptcy Code section 544(a)(3), the so-called “trustee avoiding power” or “strong arm” power. This code provision allows a trustee (or a debtor-in-possession) to avoid an interest in debtor real property that is not perfected as of the commencement of bankruptcy. (See our posting for 5/22/10, “Bankruptcy 101.”)

Fulton County Courthouse, where the questioned security deed was recorded and indexed in the land records

In this case, the trustee claimed the “first” was not entitled to be recorded in the land records, and thus “perfected,” because it did not comply with Georgia statutes requiring that a mortgage affecting real property be signed and acknowledged before a notary, attested to by the notary, and attested to by one additional witness, in order to be accepted for recording.

The bankruptcy court ruled in favor of the trustee, avoiding the mortgage and relegating the lender to status of an unsecured creditor for the $240,000 debt. The lender would stand in line for cents on the dollar.

The lender appealed, arguing that despite its flaws the mortgage was in fact recorded and correctly indexed in the land records. Anyone who searched the records should find the mortgage and readily understand it was intended to encumber the property. The lender relied on case law holding that a defective instrument once recorded may impart constructive notice of its contents.

The federal district court entertaining the appeal said the issue involved “an unclear question of Georgia law,” and asked the Georgia Supreme Court to decide whether, in Georgia, a recorded security deed with a “facially defective attestation” can provide constructive notice.

The Supreme Court sided with the bankruptcy court. The Court allowed that a “duly recorded” albeit defective instrument can provide constructive notice, but said this security deed was not duly recorded because a lack of required attestations was apparent “on the face” of the instrument. Instead, the Court cited “longstanding law” that a mortgage recorded with “facial defects as to attestation” may not impart constructive notice.

The Court concluded saying the lender’s position would relieve it and other lenders “of any obligation to present properly attested security deeds.” It would “risk an increase in fraud,” and “shift to the subsequent bona fide purchaser and everyone else the burden of determining (possibly decades after the fact) the genuineness of the grantor’s signature.”

Moral: Another example of section 544(a)(3) at work, and a reminder (if we need one) that legal formalities matter.

The case is U.S. Bank National Association v. Gordon, ___ S.E.2d ___, 2011 WL 1102995 (Ga. 2011).