First there were bad mortgages, now it’s dud foreclosures.

HAVERHILL, MA–Francis Bevilacqua was a cash-for-trash real estate investor.

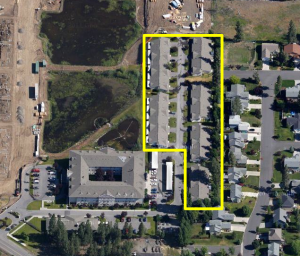

When he bought this duplex in 2006 the chain of title was, let’s say, not perfect.

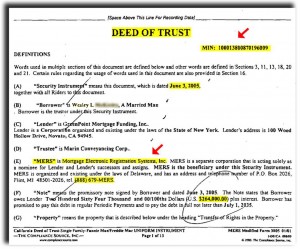

A prior owner was Pablo Rodriquez. In March 2005 Rodriquez gave a mortgage against the property to Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems (“MERS”), as nominee for the originating lender, Finance America. MERS, remember, is the privately owned database created by the mortgage banking industry to track mortgage loan ownership and servicing rights throughout the U.S. The mortgage bankers save lots of money on recording fees by registering with MERS instead of local county recording offices.

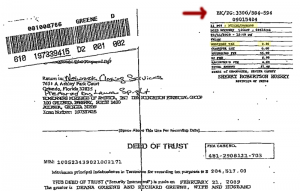

Rodriguez defaulted on his loan and in June 2006 the property was sold at a foreclosure sale. The foreclosing lender was U.S. Bank, as Trustee under a mortgage pooling and servicing agreement, and the successful bidder was also U.S. Bank. Weeks later, in July 2006, an assignment of the now-foreclosed mortgage from MERS, as nominee for Finance America, to U.S. Bank, was created (signed and dated). The assignment of mortgage was then recorded in the land records (Southern Essex Registry of Deeds).

Such were the circumstances when, in October 2006, Francis acquired the property by quitclaim deed from U.S. Bank.

By April 2010 Francis had converted the property into four condominiums and sold three units. At this point he had concerns about the title(s), so he filed suit to try title (akin to a quiet title action). He sought an order from the Massachusetts Land Court confirming his quitclaim deed, to rule out “the possibility of an adverse claim by Rodriquez.”

The Land Court ruled against Francis, even though Rodriguez could not be found and there was no opposition to the lawsuit. The court held Francis did not have standing to sue because the U.S. Bank foreclosure was void and his quitclaim deed was worthless. Francis appealed, and the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court agreed to decide the case.

The Supreme Court upheld the Land Court decision. The Court explained that at the time the foreclosure deed was created (June 29, 2006) its grantor (U.S. Bank, as Trustee) did not have an interest in the property according to “official” land records (the Southern Essex Registry of Deeds). Instead, U.S. Bank first appears in the chain of title by virtue of the assignment of mortgage (dated July 21, 2006). Since foreclosure can only be done by a mortgage holder, the foreclosure here was unauthorized, and void.

It follows the quitlclaim deed from U.S. Bank to Francis was ineffective to pass title.

Responding to Francis’ argument that he should be entitled to protected status of a bona fide purchaser, because he had no way of knowing all this, the Court disagreed saying the problem was apparent in the land records before Francis bought the property.

The Court concluded saying Francis may yet perfect his title if he can arrange a proper foreclosure to eliminate Rodriguez’s interest.

Moral: In recent years lenders and investors have relied heavily on MERS to evidence their mortgage rights. It’s been assumed an investor with superior rights can foreclose first and straighten out land records later. This decision upends such assumptions, at least in Massachusetts.

But what should such technicalities matter, when a borrower can’t afford property and abandons it?

According to the Supreme Court, it matters because the defaulting borrower continues to have a right to redeem the loan and reclaim the property, until the right of redemption is ended by foreclosure. It follows the borrower can still refinance or sell and, if he files bankruptcy, the property may be part of the debtor’s estate–tied up in bankruptcy proceedings.

Consequences of all this may seem illusory, but fear of clouded titles will cause some to avoid foreclosures entirely. And as for properties already foreclosed, and perhaps resold, no one knows how many could be in legal limbo.

State laws differ, so it’s unclear whether this view of faulty foreclosures will spread outside the Bay State.

The case is Bevilacqua v. Rodriguez, 995 N.E.2d 884 (Mass. 2011).